(A Complete Guide for Students and Clinical Research Professionals)

Every medicine that reaches a patient’s hand undergoes a long journey of research, testing, and approval. This process — known as clinical trials — ensures that drugs are safe, effective, and high-quality before being made available to the public.

Clinical trials are conducted in four main phases (I to IV), each with a specific purpose, participant group, and outcome. Understanding what happens in each phase is essential for anyone studying or working in pharmacy, life sciences, clinical research, or regulatory affairs.

Let’s explore what actually happens in Phase I, II, III, and IV clinical trials.

What Are Clinical Trial Phases?

Clinical trials are sequential steps in the drug development process, starting from testing a compound in humans for the first time to monitoring its long-term effects after approval.

Each phase answers a unique question:

Phase I: Is it safe?

Phase II: Does it work?

Phase III: Is it better than existing treatments?

Phase IV: How does it perform in the real world?

These phases are conducted as per ICH-GCP (Good Clinical Practice) and regulatory guidelines from agencies such as CDSCO (India), USFDA (USA), and EMA (Europe) etc.

Phase I – Human Pharmacology (First-in-Human Trials)

Objective

To determine safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics (PK), and pharmacodynamics (PD) of the investigational drug.

Participants

Healthy adult volunteers (usually 20–100).

(Tripathi notes exceptions for cytotoxic or toxic agents, e.g. anticancer drugs, where patients are used.)

Study Design & Activities

Single Ascending Dose (SAD) and Multiple Ascending Dose (MAD) studies.

Observation for vital signs, ECG, organ function tests, and any adverse effects.

Determination of Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) and Dose-Limiting Toxicity (DLT).

Calculation of PK parameters – Cmax, Tmax, AUC, t½, and clearance.

Outcome

Confirms safe dosage range and provides data for designing Phase II.

Tripathi describes this as establishing the “therapeutic window” of the molecule.

Phase II – Therapeutic Exploration

Objective

To assess therapeutic efficacy and short-term safety in patients suffering from the target disease.

Participants

About 100–300 patients.

(Tripathi refers to this as the “pilot therapeutic trial.”)

Study Design & Activities

Randomized, controlled studies using placebo or standard treatment.

Establishment of effective dose range (ED50) and dose–response relationship.

Recording of common side-effects and drug–drug interactions.

Often divided into:

Phase IIa: Proof-of-concept (preliminary efficacy).

Phase IIb: Dose-ranging and regimen optimization.

Outcome

Determines optimum therapeutic dose and benefit–risk ratio.

Tripathi emphasizes that many drugs fail here due to ineffective dosage or unacceptable toxicity.

Phase III – Therapeutic Confirmation (Large-Scale Trials)

Objective

To confirm efficacy and safety in a large, diverse patient population and to compare with existing therapy.

Participants

Typically 1,000 – 3,000 patients across multiple centers.

Study Design & Activities

Randomized, double-blind, multicentric controlled trials.

Evaluation of clinical endpoints (mortality, symptom improvement, biochemical parameters).

Monitoring of adverse events, drug interactions, and withdrawal rates.

Statistical validation of efficacy superiority or non-inferiority.

Preparation of full dossier (CTD Modules 2–5) for submission to regulatory authorities (CDSCO, USFDA, EMA).

Outcome

Provides the pivotal evidence for marketing authorization.

According to K.D. Tripathi, Phase III is the “critical comparative assessment” that determines whether the new drug truly improves therapy.

Phase IV – Post-Marketing Surveillance (PMS)

Objective

To detect rare, delayed, or long-term adverse effects and evaluate real-world effectiveness after the drug is marketed.

Participants

Thousands of patients using the drug in everyday practice.

Study Activities

Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) reporting via systems like PvPI (India), FAERS (US), or EudraVigilance (EU).

Observational studies, registries, and phase IV interventional trials.

Evaluation of safety in special populations – children, elderly, pregnant women.

Pharmacoeconomic analysis and patient-reported outcomes.

Outcome

Provides continuous safety monitoring; may lead to label changes, usage restrictions, or product withdrawal.

Tripathi terms this “post-marketing vigilance” — essential for ensuring a favorable long-term risk–benefit balance.

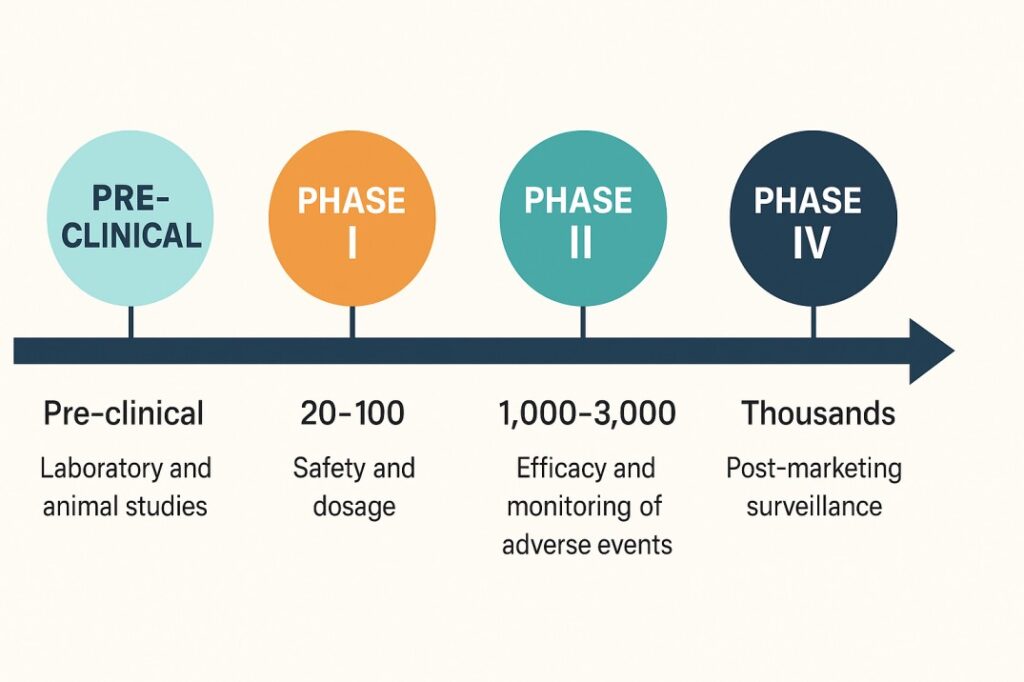

Summary of Phases I–IV (Adapted from K.D. Tripathi)

| Phase | Objective | Participants | Duration | Outcome / Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Human safety, PK/PD | 20–100 healthy volunteers | Few months | Safe dose, tolerability |

| II | Therapeutic exploration | 100–300 patients | 6 – 12 months | Effective dose, short-term safety |

| III | Therapeutic confirmation | 1,000 – 3,000+ patients | 1–4 years | Confirmed efficacy & comparative safety |

| IV | Post-marketing surveillance | Thousands (real use) | Ongoing | Long-term safety & pharmacovigilance |

Regulatory and Ethical Oversight

All phases follow:

ICH-GCP (E6 R3) principles.

Regulatory guidelines.

Ethics Committee (EC) review and Informed Consent from every participant.

Monitoring is performed by Clinical Research Associates (CRAs) and oversight by Data Safety Monitoring Boards (DSMBs) ensures volunteer protection.

Final Thoughts

The process of drug development from discovery to marketing is long, expensive, but indispensable for therapeutic advancement.”

Each clinical phase builds scientific evidence step by step — from establishing safety in volunteers to confirming real-world effectiveness. Together they guarantee that every medicine available today is safe, effective, and backed by ethical scientific validation.

Understanding these phases not only strengthens a student’s pharmacology foundation but also prepares professionals for careers in clinical research, pharmacovigilance, and regulatory affairs — where science meets patient care.